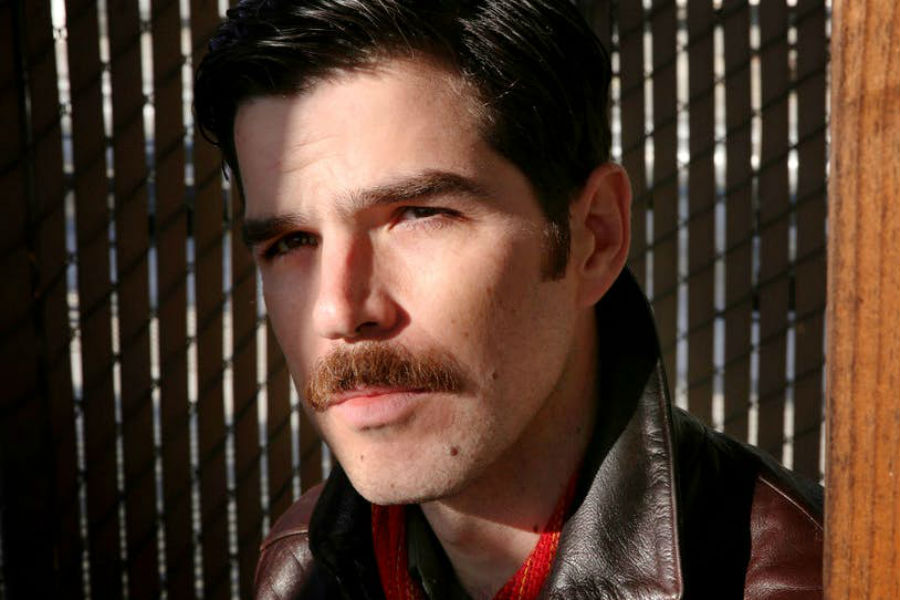

Francisco Cantú, author of The Line Becomes a River, is one of our UTV Reading Fellows in the memoir master class. Get to know him in this exclusive interview with Under the Volcano.

What books are you currently reading?

Aquí no es Miami by Fernanda Melchor, Gore Capitalism by Sayak Valencia (translated by John Pluecker), and Moon by Jennifer S. Cheng.

What books do you return to over time? Why?

I often return to certain books because of traveling to or spending time in the specific places they depict, books like Juan Rulfo’s Pedro Páramo, W. G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn, Juan Ramón Jiménez’s Platero y yo, and a whole handful of books about the borderland deserts of the Southwest where I live. Literature informs our understanding of place, and our understanding of place informs our understanding of literature, so there is a beautiful cycle that is constantly renewed by visiting and revisiting specific places and works of literature. I also always return to poetry for its distilled and timeless wisdom, poetry by women like Ofelia Zepeda, Sara Uribe, Natalie Diaz, Natalie Scenters-Zapico, and on and on.

Which three writers, dead or alive, would you like to have coffee or drinks with? Why?

Maybe this is cheating, but I’d love to have a three-way conversation with Juan Rulfo and Cristina Rivera Garza over a bottle of mezcal. Honestly, I would even be satisfied to just be a fly on the wall during a meeting between those two. I’ve recently finished Rivera Garza’s book on Rulfo, in which she visits many of the places he wrote about or worked in, including the real-life Luvina—today half of the village’s residents live in Los Angeles. To hear Rulfo’s understanding of what Mexico was paired with Rivera Garza’s understanding of what Mexico has become would fascinate me to no end. My third writer would be W. G. Sebald, who died in 2001. I’d love to have a beer with him to mine his circuitous and sideways understanding of violence and the impression it forever leaves in landscape and in culture.

Do you have a secondary passion or talent apart from writing that might surprise people to know about?

I’m weirdly passionate about ethnobotany of agave, particularly in Arizona and Sonora, and am a mezcal obsessive and have even been able to learn a lot about the production process by occasionally helping different people harvest, roast, mash, ferment, and distill.

If you could offer three tips to writers what would they be?

Here’s a single piece of advice that contains three separate tips: First, be gentle with yourself by understand that you don’t have to be sitting in front of a computer to be doing important “writing” work. If you’re stuck in your writing process, pick up a book that has something to do with what your writing about (however obliquely), and read that instead. If that doesn’t work, go on a walk. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve stared at a blank screen or a jumbled assortment of notes and felt paralyzed to say or make sense of anything, just to find myself inspired as soon as I pick up someone else’s work or take a moment to connect with the outside world.

What is your writing routine?

For serious generative writing sessions, I find that I really need to seek out extended periods of solitude away from the city where I live. I’ll go away for 3-4 days to write wherever I can—a traveling family member’s empty house, a remote rental cabin or Airbnb, the little trailer I have parked on a piece of land my mom owns in northern Arizona, or at a writing residency when I’m fortunate enough to have one.

What was your moment of greatest despair as a writer and how did you get out of it?

Before I was a published writer I had my car broken into and a duffel bag stolen. Some clothes were in there, an iPod, and a journal with years’ worth of notes and writing. There was all sorts of experiences and reflections and travels in there that I thought were lost forever. I put up these signs all around the neighborhood “black journal stolen from car, please return, cash reward, no questions asked.” A few days later I got a call from a woman who had found the journal in a pile of trash next to a dumpster in a nearby church parking lot. She said it caught her eye as she was walking to her car after bible study. It seemed like a strange thing for someone to throw away, so she opened it up and found my name and number on the front page. She wouldn’t take any money, but I’ll never forget that woman—I still send her thoughts of gratitude from time to time. Despite all my effort with the signs, she never saw one, so I guess the lesson here is to always put your name and number on the first page of your journal.